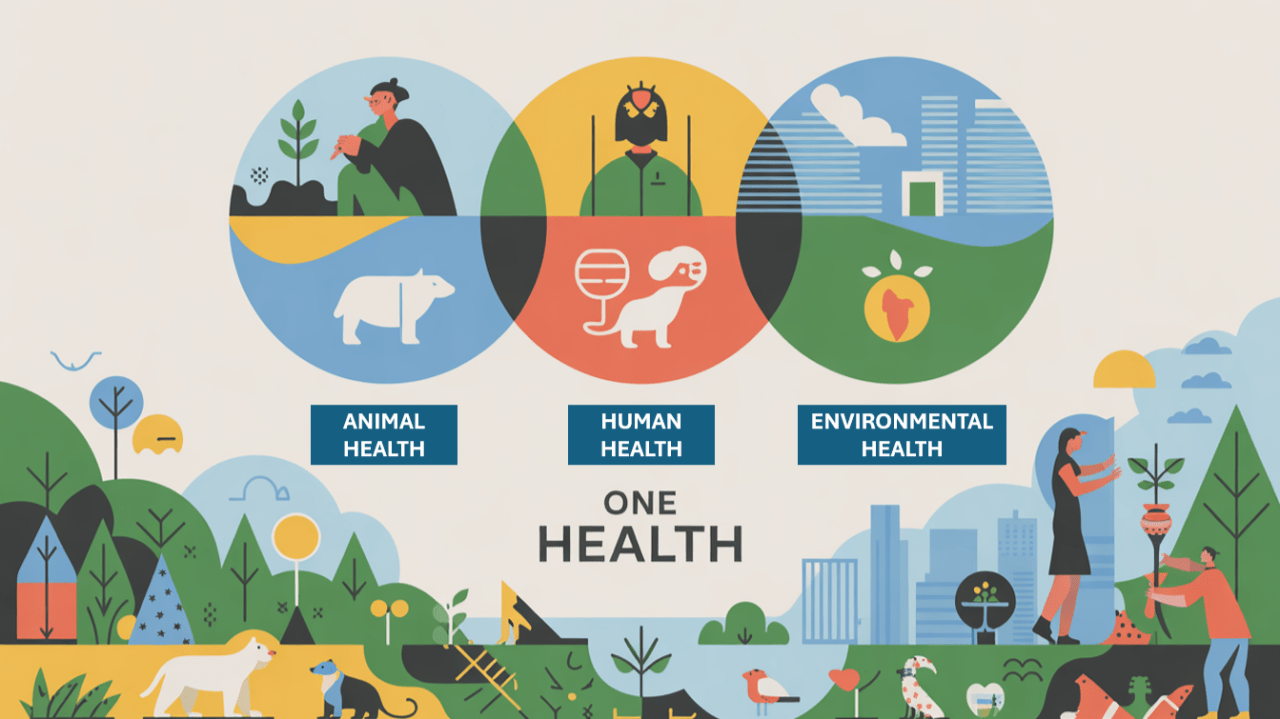

The One Health concept emphasizes the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health. It has evolved into a multidisciplinary framework addressing complex health challenges such as zoonotic diseases, antimicrobial resistance, and food safety, through interdisciplinary collaboration and systems thinking.

Foundations and scope

One Health emerged from the recognition that human health cannot be isolated from animal and ecosystem health. Historically, zoonotic outbreaks such as rabies and avian influenza underscored the need for integrated surveillance and response systems (Schneider et al., 2019). Today, One Health is recognized globally as a strategic framework for preventing and controlling health threats at the human-animal-environment interface through interdisciplinary collaboration (Couto & Brandespim, 2020).

Acknowledging the need for cross-disciplinary and multinational collaboration, four leading global organizations established the One Health Quadripartite: the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly OIE), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (Pitt & Gunn, 2024; Vors et al., 2024).

Key operational areas include (Benis et al., 2021; Couto & Brandespim, 2020; Marinas et al., 2024; Pitt & Gunn, 2024):

a) Zoonotic Diseases

Zoonotic diseases (pathogens transmitted between animals and humans), represent over 60% of known infectious diseases and 75% of emerging infectious diseases. Examples include rabies, avian influenza, brucellosis, anthrax, and Ebola.

The One Health approach promotes:

- Integrated surveillance systems connecting human, animal, and wildlife health data for early detection.

- Joint outbreak investigations and rapid response mechanisms.

- Vaccination and vector control programs that cover both animal and human populations.

- Wildlife monitoring and trade regulation, reducing spillover events from high-risk interfaces.

- Community engagement to promote behavioral changes that prevent zoonotic transmission.

Zoonotic disease prevention aligns with pandemic preparedness strategies, highlighting One Health as an essential pillar of global health security.

b) Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs)

NTDs (such as leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, echinococcosis, and trypanosomiasis) affect more than a billion people, primarily in low- and middle-income countries. Many NTDs involve vectors or animal reservoirs, making a One Health approach vital for their control.

Key actions include:

- Vector control programs integrating environmental and agricultural practices.

- Joint veterinary–public health interventions, such as dog vaccination campaigns for rabies elimination.

- Improved water, sanitation, and hygiene combined with animal waste management.

- Community-based surveillance and integrated disease mapping to identify co-endemic areas.

- Multisectoral research collaborations to understand transmission dynamics at the local ecosystem level.

c) Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

AMR is a global One Health crisis, threatening modern medicine, agriculture, and food production. Resistant pathogens circulate between humans, animals, plants, and the environment through water, soil, food, and waste systems.

The One Health approach addresses AMR by:

- Promoting antimicrobial stewardship in human and veterinary medicine.

- Regulating antimicrobial use in food-producing animals.

- Strengthening laboratory surveillance networks, using harmonized AMR monitoring protocols.

- Enhancing wastewater and environmental monitoring for resistant genes.

- Encouraging innovation in alternatives to antibiotics, such as vaccines, probiotics, and improved biosecurity.

d) Food Safety

Ensuring safe food production and supply chains requires coordination between public health, veterinary, and environmental sectors. Contaminated food contributes to over 600 million illnesses and 420,000 deaths annually.

One Health contributes by:

- Strengthening food inspection and traceability systems.

- Integrating zoonotic surveillance along the entire food chain—from farm to fork.

- Reducing contamination risks through sustainable agricultural practices and responsible pesticide use.

- Addressing foodborne antimicrobial resistance via integrated residue monitoring.

- Promoting sustainable food production, reducing environmental impact and ensuring nutrition security

e) Environmental Health

Environmental degradation, biodiversity loss, and climate change are major drivers of disease emergence. These disruptions alter habitats, force wildlife closer to human populations, and change vector dynamics, creating new opportunities for pathogens to spill over from animals to humans.

Key One Health interventions include:

- Land-use planning to balance agricultural, urban, and conservation priorities.

- Biodiversity conservation to maintain ecosystem services and pathogen regulation.

- Climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies integrated into health planning.

- Pollution control and waste management, reducing chemical and microbial contamination.

- Ecosystem monitoring, such as tracking temperature, rainfall, and vector population shifts that affect disease transmission.

A deep understanding of these interconnected ecological dynamics is crucial for anticipating disease emergence, conducting accurate risk assessments, and implementing proactive prevention strategies within an integrated One Health framework.

f) Laboratory and Diagnostic Capacity

Reliable diagnostics and data-sharing networks form the backbone of One Health implementation. Core components include:

- Interconnected laboratory systems across medical, veterinary, and environmental institutions.

- Standardized diagnostic protocols and biosafety practices.

- Genomic surveillance platforms for pathogen tracking and evolutionary analysis.

- Interoperable databases and digital tools for real-time information exchange.

- Training programs to build laboratory and field epidemiology capacity.

Stronger diagnostic networks support early detection, evidence-based decision-making, and rapid outbreak containment.

Challenges and Future Directions

Although One Health offers significant promise, its implementation is hindered by systemic challenges, including weak governance, limited resources, and insufficient integration of social sciences (Vors et al., 2024; Yopa et al., 2023).

Operationalization further requires overcoming barriers related to resource allocation, policy alignment, and fostering meaningful collaboration among diverse stakeholders. Monitoring and evaluation frameworks remain underdeveloped, and trade-offs between human, animal, and environmental health often complicate progress, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Addressing these gaps calls for strategic solutions, capacity building, and innovative approaches to ensure equitable and sustainable outcomes (Degeling et al., 2015; Ribeiro et al., 2019; Rüegg et al., 2017; Rüegg et al., 2018).

REFERENCES

Benis, A., Tamburis, O., Chronaki, C., & Moen, A. (2021). One Digital Health: A Unified Framework for Future Health Ecosystems. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23. https://doi.org/10.2196/22189

Couto, R. de M., & Brandespim, D. F. (2020). A review of the One Health concept and its application as a tool for policy-makers. International Journal of One Health, 6(1), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.14202/IJOH.2020.83-89

Degeling, C., Johnson, J., Kerridge, I., Wilson, A., Ward, M., Stewart, C., & Gilbert, G. (2015). Implementing a One Health approach to emerging infectious disease: reflections on the socio-political, ethical and legal dimensions. BMC Public Health, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2617-1

Marinas, I. C., Buica, A., Oprea, E., & Chifiriuc, M. C. (2024). Editorial: Zoonotic antimicrobial resistance and virulence: One Health integrated approaches to monitor and reduce food chain hazards. Frontiers in Microbiology, 15, 1478509. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1478509

Pitt, S., & Gunn, A. (2024). The One Health Concept. British Journal of Biomedical Science, 81. https://doi.org/10.3389/bjbs.2024.12366

Ribeiro, C., Van De Burgwal, L., & Regeer, B. (2019). Overcoming challenges for designing and implementing the One Health approach: A systematic review of the literature. One Health, 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2019.100085

Rüegg, S., McMahon, B., Häsler, B., Esposito, R., Nielsen, L., Speranza, C., Ehlinger, T., Peyre, M., Aragrande, M., Zinsstag, J., Davies, P., Mihalca, A., Buttigieg, S., Rushton, J., Carmo, L., De Meneghi, D., Canali, M., Filippitzi, M., Goutard, F., Ilieski, V., Milićević, D., O’Shea, H., Radeski, M., Kock, R., Staines, A., & Lindberg, A. (2017). A Blueprint to Evaluate One Health. Frontiers in Public Health, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00020

Rüegg, S., Nielsen, L., Buttigieg, S., Santa, M., Aragrande, M., Canali, M., Ehlinger, T., Chantziaras, I., Boriani, E., Radeski, M., Bruce, M., Queenan, K., & Häsler, B. (2018). A Systems Approach to Evaluate One Health Initiatives. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2018.00023

Schneider, M. C., Munoz-Zanzi, C., Min, K., & Aldighieri, S. (2019). “One Health” from concept to application in the global world. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.29

Vors, L., Raboisson, D., & Lhermie, G. (2024). Analysis of convergence between a unified One Health policy framework and imbalanced research portfolio. Discover Public Health, 21(33). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00159-0

Yopa, D. S., Massom, D. M., Kiki, G. M., Sophie, R. W., Fasine, S., Thiam, O., Zinaba, L., & Ngangue, P. (2023). Barriers and enablers to the implementation of one health strategies in developing countries: a systematic review. Frontiers in public health, 11, 1252428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1252428